And taxes shall have no dominion

This blog often concerns itself with death, but not so much with that other unyielding constant of life, taxes. Inspired by a conversation with my friend Will, I’ve decided to rectify that imbalance. Apart from complaints, what is there to say about taxes? Economic theory says they should:

Income taxes and corporate taxes are usually progressive, but are also much easier to evade (especially for the super-wealthy), and penalise productive work on both an individual and a corporate level. More on them later. Carbon taxes can also be dodged, but are otherwise ideal because the thing they disincentivise is a major negative externality - I hope they become more widespread soon.

Land taxes

- Be very difficult to evade.

- Not disincentivise the production of things we actually want.

- Be progressive - ideally in percentage terms, but at least in absolute terms.

Income taxes and corporate taxes are usually progressive, but are also much easier to evade (especially for the super-wealthy), and penalise productive work on both an individual and a corporate level. More on them later. Carbon taxes can also be dodged, but are otherwise ideal because the thing they disincentivise is a major negative externality - I hope they become more widespread soon.

Land taxes

How about a land value tax? That is, a tax proportional to the value of the land you own - not counting the value of the buildings on that land. It's incredibly difficult to evade - you can't hide your land from the government. It's progressive, because wealthy people tend to own much more land - and by targeting a major source of hereditary wealth, it would reduce inequality more directly and fairly than income taxes. Lastly, it doesn't disincentivise the production of land, because you can't produce land (except via reclamation projects, I guess, but I'm sure an exception could be made for those). In fact, since the tax is equal no matter how well or badly the land is used, it encourages landowners to develop their land, rather than holding it for speculation.

Let's explore that last point a little more. You might think that the lost revenue from leaving a lot empty is enough of a disincentive to prevent it. But construction is very expensive and time-consuming - partly for regulatory reasons (which I detail here) but also because the sort of buildings which bring in revenue in city centers - apartment blocks and skyscrapers - are necessarily large projects. Given how much property prices are rising in cities, you can often make a handsome profit just by hanging on to land for a few years (maybe while using it as a parking lot) without the same cash outlay, time commitment and risk required for a major development.

This is bad, because bustling, vibrant central districts are important to making cities great, and great cities are a public good. Such cities collect and connect clever people to make them more productive and innovative. This has been true for millennia, from the city-states of Ancient Greece to the trading hubs of Renaissance Italy to the glamorous European capitals of the 19th and 20th centuries. It may be even more true now, as winner-takes-all dynamics increase the returns to being in the best locations. More development of city centres would also decrease urban sprawl and all its concomitant problems (long commutes, racially-segregated suburbs, carbon emissions, etc).

There are still some problems with a land value tax. The main theoretical one is that it requires the government to assess underlying land values. Unlike overall property prices, there's no clear market mechanism for doing so, and there's a pretty strong incentive for governments to be optimistic about values when doing evaluations. A second problem is that it makes some projects, like private parks, much costlier. While it would be fairly easy to exempt these, it'd be dangerous to set a precedent of allowing exceptions, which could screw up land allocation. And in fact there's at least one exception which would do so, and also seems quite likely to be included in any proposed land tax - namely, an exemption for primary residences. These are already excluded from the UK's inheritance tax, because otherwise heirs would usually have to sell them to pay the tax. Similarly, the many retirees for whom their house is their major asset would struggle to pay even a small percentage of its land value every year directly out of their incomes.

To be clear, in economic terms this is a feature not a bug. Individual houses are a very unproductive use of central land, but they often can't be put to better use because their owners want to keep living in them for a period of decades. So putting a bit more pressure on them to move speeds up growth. But it's not too coercive, because even income-poor owners could afford to stay if they really wanted to by taking a loan with the house as collateral. Unfortunately, that's the sort of option which people are fairly biased against. And since the elderly are a disproportionately influential voting bloc, I'd bet that a land tax would come bundled with a primary residence exemption. But if other types of building are taxed and those aren't, the net effect might be more of city centers being used unproductively. I guess this would vary by city - London might be fine, since it's nigh-impossible for individuals to buy central land outright. However, that's partly because over 1000 acres of prime real estate is owned by “the Crown, the Church, and five aristocratic estates with a collective wealth of £22 billion.” Any guesses who'd be first in line for exemptions from a land tax? Which is a real shame - I'm usually not in favour of radical wealth redistribution but as far as I can tell these aristocratic estates are pure rentiers who contribute nothing except inequality.

On the other hand, I'm generally loath to recommend the government institute another tax, because even though it'd be an improvement if it replaced an existing one, in practice it's quite likely that both end up coexisting, increasing the overall tax burden. The belief that governments are actually very bad at making use of the taxes they receive is one I’ve had for quite some time, although I admit that its emotional impact rose sharply when I realised just how much of my income I'll be losing to tax next year. (I wouldn't mind nearly as much if I thought the money would actually improve other people's lives - thank goodness charitable donations are tax deductible).

Corporate taxes

I think it's reasonable to say that corporate taxes haven't been working very well lately. Corporations have become incredibly adept at manipulating complex tax laws across many countries to their advantage - and so far the international community has been pretty impotent in taking measures to prevent that. Even when companies can't avoid nominally high taxes, they often leave their money offshore until a "tax holiday" is declared, so effective taxes end up being much lower. In fact, the global average corporate tax rate has fallen from 49% to 24% over the past three decades.

Is this even such a bad thing, though? Corporate tax is a form of double taxation - whatever profits companies earn will eventually translate to gains for their shareholders, who are then taxed again as individuals. (In fact, for multinationals it’s often triple taxation: once in the country where the income is earned, again in their home country, and again when profits are distributed.) So in theory, the total amount collected could be the same whether or not corporations are taxed at all. However, it would be collected by different countries - not the ones in which profits are made, but the ones in which the owners of multinationals are clustered, i.e. mainly America and China. (And if those owners moved to income tax havens, perhaps nobody would be collecting tax from them at all.)

On the other hand, the status quo isn't much better when it comes to fair distribution of corporate taxes. As the graph below shows, the efficacy of corporate tax collection for US tech giants is very low outside the US. Ian Hogarth thinks that the unevenness of corporate tax will be a major concern for other countries as these companies start to automate more and more jobs and therefore constitute a greater share of the global economy. Kai-Fu Lee suggests that such countries will need to become "economic dependents" of the US or China to avoid poverty after their jobs are lost.

AI and taxes

Interestingly, Lee's conclusion that "the solution to the problem of mass unemployment ... will involve ""service jobs of love" ... [which are] jobs that A.I. cannot do, that society needs and that give people a sense of purpose" is pretty similar to my own thinking on the issue. The main difference is that I think these jobs will be financed by wealth increases across society overall, as professional sports teams are, rather than by top-down subsidies. This is informed by my broader belief that, even if the wealth created by technological innovation isn't distributed equally, it'll still benefit the vast majority of people. This has held true for almost all technological developments so far, even ones which seemed elitist when introduced (e.g. the iPhone, which hastened the arrival of budget smartphones). Artificial general intelligence (AGI) may be an extreme enough case that it's an exception to this principle, but I doubt narrow AI is. In fact, it's much easier for poor countries to cultivate CS expertise than other forms of scientific or technological expertise - and even as budgets for computing power shoot up, talent is still the biggest limiting factor. Note also that there’s intense competition in the tech sector, to the point where companies often have to give away valuable software (like map apps or email services) for free, because if they don’t, they’ll be undercut by competitors who do. Assuming that this trend continues - and I see no reason why it won’t - the percentage of the social value of their innovations captured by tech companies will continue to be very low, with most of that value instead going to people across the world.

Nevertheless, it's worth taking Hogarth and Lee's concerns seriously, because even narrow AI has the potential to replace so many jobs; because cutting-edge AI capabilities do seem to be pretty heavily consolidated in a few firms in a few countries; and because worsening international inequality could cause serious global instability. On the other hand, it's very unclear what can be done. Hogarth suggests that countries like the UK and South Korea develop and protect their own AI industries - but at best this extends the potential AI duopoly to an oligopoly. There's a case for openly publishing AI research (which is standard across top research groups) and open-sourcing libraries and training environments (which isn't, although OpenAI seems committed to doing so) - but I worry that these measures increase the risk of catastrophic AI outcomes by allowing wider access to dangerous technology. There's no easy trade-off here, but I am inclined to be more concerned about extreme scenarios which could harm the long-term future of the human race, even if focusing on these increases inequality.

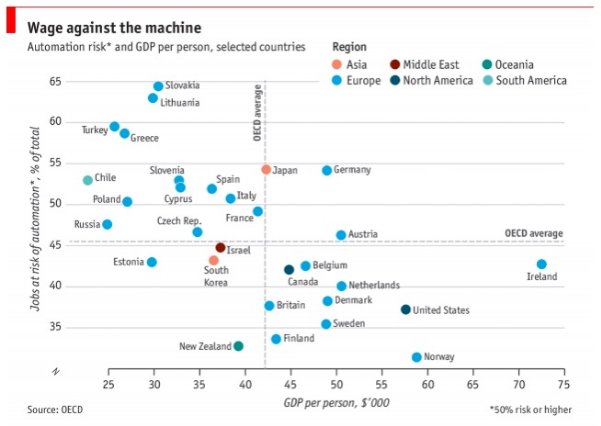

Lastly, there’s the question about which countries will be hit hardest by automation. Hogarth cites the following chart, which claims that amongst OECD countries, poorer ones will lose a greater proportion of their jobs. However, this trend probably reverses when we consider much poorer countries in which the workforces haven't transitioned to white-collar jobs, and where wages are low enough that it's difficult for robots to displace workers. And if the global poor aren't losing their jobs but still indirectly gain the benefits of, say, AI-enhanced R&D inventing better medicines or energy sources, that seems like a good outcome.

Corporate incentives

Let's explore that last point a little more. You might think that the lost revenue from leaving a lot empty is enough of a disincentive to prevent it. But construction is very expensive and time-consuming - partly for regulatory reasons (which I detail here) but also because the sort of buildings which bring in revenue in city centers - apartment blocks and skyscrapers - are necessarily large projects. Given how much property prices are rising in cities, you can often make a handsome profit just by hanging on to land for a few years (maybe while using it as a parking lot) without the same cash outlay, time commitment and risk required for a major development.

This is bad, because bustling, vibrant central districts are important to making cities great, and great cities are a public good. Such cities collect and connect clever people to make them more productive and innovative. This has been true for millennia, from the city-states of Ancient Greece to the trading hubs of Renaissance Italy to the glamorous European capitals of the 19th and 20th centuries. It may be even more true now, as winner-takes-all dynamics increase the returns to being in the best locations. More development of city centres would also decrease urban sprawl and all its concomitant problems (long commutes, racially-segregated suburbs, carbon emissions, etc).

There are still some problems with a land value tax. The main theoretical one is that it requires the government to assess underlying land values. Unlike overall property prices, there's no clear market mechanism for doing so, and there's a pretty strong incentive for governments to be optimistic about values when doing evaluations. A second problem is that it makes some projects, like private parks, much costlier. While it would be fairly easy to exempt these, it'd be dangerous to set a precedent of allowing exceptions, which could screw up land allocation. And in fact there's at least one exception which would do so, and also seems quite likely to be included in any proposed land tax - namely, an exemption for primary residences. These are already excluded from the UK's inheritance tax, because otherwise heirs would usually have to sell them to pay the tax. Similarly, the many retirees for whom their house is their major asset would struggle to pay even a small percentage of its land value every year directly out of their incomes.

To be clear, in economic terms this is a feature not a bug. Individual houses are a very unproductive use of central land, but they often can't be put to better use because their owners want to keep living in them for a period of decades. So putting a bit more pressure on them to move speeds up growth. But it's not too coercive, because even income-poor owners could afford to stay if they really wanted to by taking a loan with the house as collateral. Unfortunately, that's the sort of option which people are fairly biased against. And since the elderly are a disproportionately influential voting bloc, I'd bet that a land tax would come bundled with a primary residence exemption. But if other types of building are taxed and those aren't, the net effect might be more of city centers being used unproductively. I guess this would vary by city - London might be fine, since it's nigh-impossible for individuals to buy central land outright. However, that's partly because over 1000 acres of prime real estate is owned by “the Crown, the Church, and five aristocratic estates with a collective wealth of £22 billion.” Any guesses who'd be first in line for exemptions from a land tax? Which is a real shame - I'm usually not in favour of radical wealth redistribution but as far as I can tell these aristocratic estates are pure rentiers who contribute nothing except inequality.

On the other hand, I'm generally loath to recommend the government institute another tax, because even though it'd be an improvement if it replaced an existing one, in practice it's quite likely that both end up coexisting, increasing the overall tax burden. The belief that governments are actually very bad at making use of the taxes they receive is one I’ve had for quite some time, although I admit that its emotional impact rose sharply when I realised just how much of my income I'll be losing to tax next year. (I wouldn't mind nearly as much if I thought the money would actually improve other people's lives - thank goodness charitable donations are tax deductible).

Corporate taxes

I think it's reasonable to say that corporate taxes haven't been working very well lately. Corporations have become incredibly adept at manipulating complex tax laws across many countries to their advantage - and so far the international community has been pretty impotent in taking measures to prevent that. Even when companies can't avoid nominally high taxes, they often leave their money offshore until a "tax holiday" is declared, so effective taxes end up being much lower. In fact, the global average corporate tax rate has fallen from 49% to 24% over the past three decades.

Is this even such a bad thing, though? Corporate tax is a form of double taxation - whatever profits companies earn will eventually translate to gains for their shareholders, who are then taxed again as individuals. (In fact, for multinationals it’s often triple taxation: once in the country where the income is earned, again in their home country, and again when profits are distributed.) So in theory, the total amount collected could be the same whether or not corporations are taxed at all. However, it would be collected by different countries - not the ones in which profits are made, but the ones in which the owners of multinationals are clustered, i.e. mainly America and China. (And if those owners moved to income tax havens, perhaps nobody would be collecting tax from them at all.)

On the other hand, the status quo isn't much better when it comes to fair distribution of corporate taxes. As the graph below shows, the efficacy of corporate tax collection for US tech giants is very low outside the US. Ian Hogarth thinks that the unevenness of corporate tax will be a major concern for other countries as these companies start to automate more and more jobs and therefore constitute a greater share of the global economy. Kai-Fu Lee suggests that such countries will need to become "economic dependents" of the US or China to avoid poverty after their jobs are lost.

AI and taxes

Interestingly, Lee's conclusion that "the solution to the problem of mass unemployment ... will involve ""service jobs of love" ... [which are] jobs that A.I. cannot do, that society needs and that give people a sense of purpose" is pretty similar to my own thinking on the issue. The main difference is that I think these jobs will be financed by wealth increases across society overall, as professional sports teams are, rather than by top-down subsidies. This is informed by my broader belief that, even if the wealth created by technological innovation isn't distributed equally, it'll still benefit the vast majority of people. This has held true for almost all technological developments so far, even ones which seemed elitist when introduced (e.g. the iPhone, which hastened the arrival of budget smartphones). Artificial general intelligence (AGI) may be an extreme enough case that it's an exception to this principle, but I doubt narrow AI is. In fact, it's much easier for poor countries to cultivate CS expertise than other forms of scientific or technological expertise - and even as budgets for computing power shoot up, talent is still the biggest limiting factor. Note also that there’s intense competition in the tech sector, to the point where companies often have to give away valuable software (like map apps or email services) for free, because if they don’t, they’ll be undercut by competitors who do. Assuming that this trend continues - and I see no reason why it won’t - the percentage of the social value of their innovations captured by tech companies will continue to be very low, with most of that value instead going to people across the world.

Nevertheless, it's worth taking Hogarth and Lee's concerns seriously, because even narrow AI has the potential to replace so many jobs; because cutting-edge AI capabilities do seem to be pretty heavily consolidated in a few firms in a few countries; and because worsening international inequality could cause serious global instability. On the other hand, it's very unclear what can be done. Hogarth suggests that countries like the UK and South Korea develop and protect their own AI industries - but at best this extends the potential AI duopoly to an oligopoly. There's a case for openly publishing AI research (which is standard across top research groups) and open-sourcing libraries and training environments (which isn't, although OpenAI seems committed to doing so) - but I worry that these measures increase the risk of catastrophic AI outcomes by allowing wider access to dangerous technology. There's no easy trade-off here, but I am inclined to be more concerned about extreme scenarios which could harm the long-term future of the human race, even if focusing on these increases inequality.

Lastly, there’s the question about which countries will be hit hardest by automation. Hogarth cites the following chart, which claims that amongst OECD countries, poorer ones will lose a greater proportion of their jobs. However, this trend probably reverses when we consider much poorer countries in which the workforces haven't transitioned to white-collar jobs, and where wages are low enough that it's difficult for robots to displace workers. And if the global poor aren't losing their jobs but still indirectly gain the benefits of, say, AI-enhanced R&D inventing better medicines or energy sources, that seems like a good outcome.

Corporate incentives

Overall, we should probably think of corporate taxes as a useful form of international redistribution, and try to strengthen the ability of poorer countries in particular to collect them. In theory, I don’t think this even requires much international coordination, since tax havens aren’t useful without the domestic legal loopholes which allow them to be exploited. However, if only a few countries crack down on those loopholes, they may create pretty significant incentives for multinationals to base themselves elsewhere. I also don’t see any good way to prevent the sort of competition between polities which we saw when Amazon was deciding where to build their new HQ, because that involves local governments offering benefits to companies at their own expense. But as long as those concessions are limited to a few major hubs for each big company, that’s arguably a good thing, since it lowers the tax burden on activities like R&D and expanding global operations.

The last question is whether businesses will actually do those things if they get more money through tax cuts. Oddly enough, it seems not. Over the last few decades, corporations have started to hold much larger cash reserves than they did previously. This is particularly true for the big tech companies - over 25% of Apple’s trillion-dollar valuation is in the form of cash or short-term investments (most of it currently held overseas, although it’s being brought back soon). What makes this even more surprising is that interest rates are very low - surely there’s some way to get more than 2% return on this money? Normally more profitable investments could be found in developing countries - but these days fast-growing China invests much more in the slow-growing US than the other way round. And when Western corporations do spend their money, it’s often on share buybacks to benefit their shareholders. To be fair, the tech titans are also spending exorbitant amounts on research (Amazon leading the pack at $23 billion last year), and so perhaps the gains from that are starting to level off. But all in all, it’s a peculiar situation which I’d quite like to understand better.

The last question is whether businesses will actually do those things if they get more money through tax cuts. Oddly enough, it seems not. Over the last few decades, corporations have started to hold much larger cash reserves than they did previously. This is particularly true for the big tech companies - over 25% of Apple’s trillion-dollar valuation is in the form of cash or short-term investments (most of it currently held overseas, although it’s being brought back soon). What makes this even more surprising is that interest rates are very low - surely there’s some way to get more than 2% return on this money? Normally more profitable investments could be found in developing countries - but these days fast-growing China invests much more in the slow-growing US than the other way round. And when Western corporations do spend their money, it’s often on share buybacks to benefit their shareholders. To be fair, the tech titans are also spending exorbitant amounts on research (Amazon leading the pack at $23 billion last year), and so perhaps the gains from that are starting to level off. But all in all, it’s a peculiar situation which I’d quite like to understand better.

Comments

Post a Comment